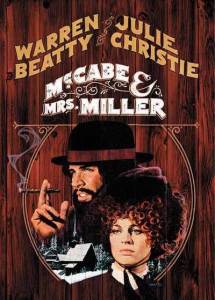

McCabe & Mrs. Miller is high on most lists of the greatest westerns of all time, especially as a prime example of the so-called revisionist western. As a fan of western movies, I would be remiss if I didn’t experience it. In honesty I didn’t expect to enjoy it as much as the sprawling, adventurous westerns that tend to be my favorites, but I had an open mind. My resulting experience was actually much more disappointing than expected. In its favor it is well-made and well-acted. On the other hand, there’s nothing at all to actually like about the film, at least for me.

McCabe & Mrs. Miller is high on most lists of the greatest westerns of all time, especially as a prime example of the so-called revisionist western. As a fan of western movies, I would be remiss if I didn’t experience it. In honesty I didn’t expect to enjoy it as much as the sprawling, adventurous westerns that tend to be my favorites, but I had an open mind. My resulting experience was actually much more disappointing than expected. In its favor it is well-made and well-acted. On the other hand, there’s nothing at all to actually like about the film, at least for me.

Setting: a Pacific Northwest mining town in the wet, dark Pacific Northwest winter. Characters: McCabe is a selfish, amoral idiot who thinks he’s a smooth business-man and Mrs. Miller is a self-important prostitute. The rest of the characters are solely concerned with drinking and whoring, are whores themselves, or are greedy businessmen. There is nothing in the story, characters, or environment that strikes me as worthy to be put to screen. Leonard Cohen’s score would be nice if it were applied to a different movie. His earthy, slice-of-life songs bring to mind a poetically sympathetic every-man who is perhaps on the path to tragedy. It is true that the characters are on the path to tragedy, but there is nothing poetic or sympathetic about them.

Out of curiosity I’ve read many reviews in an effort to understand what people are enjoying about this movie. What are they getting out of it? I gather that it mainly boils down to this: it eviscerates the western genre, as if the traditional western was pathetic and low-brow, out-moded and needing to be taken to the glue factory. For instance, McCabe & Mrs. Miller tops Timeout London’s top westerns of all time at #1, and they put it this way: “By the early 1970s, the western had boxed itself into a canyon…. It was only by breaking the western down and reassembling it bit by bit that it could break new ground.” I disagree, but you gathered that already. It later goes on, “It’s also an extraordinarily beautiful film. Altman offers a portrait of the west that’s dingy, grimy, hazy, stinky and chilled to the bone.” However, to me those last two juxtaposed sentences don’t mesh with each other at all.

Don’t get me wrong, I do enjoy some revisionist westerns, but McCabe and Mrs. Miller takes revisionism to the extreme. Wide expanses and beautiful scenery? Substitute a dark, cold, wet, miserable environment. Characters who have – or grow to have – nobility or responsibility? Substitute characters with nothing redeemable or attractive. A story with meaning or morals? Substitute a story with nothing to be drawn to, appreciated, or learned from. Truth is, I have a hard time seeing this as a western at all.

I can understand not enjoying traditional westerns, for whatever reason. Perhaps many can be seen as formulaic or sappy. But I feel that to enjoy McCabe & Mrs. Miller requires an active hate for Westerns, which fuels one to sit through two hours of ugliness. I’m sure this isn’t true, but it’s the only way my tiny brain can rationalize it at the moment.