Caution: this post is rife with spoilers for the movie. If you haven’t seen it yet, I strongly suggest you watch it first, and then read this. I’ve love to hear what people think.

Normally it’s my intention to avoid overly pontificating over the highs and lows of a films quality, or to try to get wrapped up in pretentious presentation in a thinly veiled move to show people I know more about movies than them. I don’t enjoy people who talk or act that way, and it’s not a behavior I hope to be known for. But with the Homesman I do want to break a bit from my more casual approach of discussing movies, and offer an actual breakdown of what I got out of this great film.

There are a lot of reasons for considering the Homesman to be a great western. Items and details such as the language (particularly the swearing by Tommy Lee Jones when he curses the hotel owner), the weapons, even the paper town of Fairfield where the hotel is located, all lend to an accurate view of the era. The paradox of this is that due to a lot of these great elements people walk away enjoying it, in spite of the fact that many are confused by what they saw, or what the point of it all was.

I can’t speak for others, and I’m not the type to tell you how to feel, but I hope that my breakdown opens up some thoughts on how to receive this story.

So why do people get confused? First off, the movie was highly touted as a feminist western, but given that the movie is about women gone crazy because of the strain, and the fourth woman, the strong one, ending up killing herself after exposing herself as weak and desperate, how can that be? Given these portrayals, in the end, you would have to wonder what happened along the way. The problem with this line of thought is that it’s not a feminist western.

It does uniquely give the female perspective, and that is worth much more than a feminist fantasy brought to life, but this female view to the times is not the crux of the story; it’s a catalyst for what is. It should be noted, however, that this insightful and thoughtful woman’s perspective is another authentic quality of the era that makes the Homesman such a good movie.

Another point that I’ve heard made is that after switching focus from the female lead to the male (from Swank to Jones), people are confused as to what the point of Tommy Lee Jones’ journey was other than to maybe feel good about his eventual kind gestures.

What I have gotten out of this movie is that it is a tale of the western frontier, and of the times, through the embodiment of one central male figure. It is the story of the western man who survived the west, but came and went with the progress of days. Who had only a single moment in time that he was in his right place, and that time and place didn’t last long. Which, incidentally, I also believe is why westerns are loved so much.

Initially we’re introduced to Mary Bee Cuddy (Swank) and are set up to sympathize with her situation. It’s an impressive thing she offers to do and she’s easy to get on board with, but then she meets George Briggs and things are getting ready to shift. I believe that shift came once she asks him his name. He’s introduced to the audience as just a shifty drifter, possibly a good guy, possibly a bad guy; yes, he may have claim jumped, but beyond that he’s just a western character drifting in to the lives of those already established.

When Mary asks him what his name is he thinks up a name and offers George Briggs. He laughs as he says it, amused, and it clearly doesn’t mean a lot to him. But this is something I’ll come back to.

I’m going to revisit those previous obstacles but first consider his arrival to Iowa. The purpose of this trip was to get these women back to where they can be cared for, and where is that? Back in civilization because the west was too tough. After all that George has been through he has finally made it to civilization. He delivers the women, buys new clothes, and even a nice tombstone for Mary Bee Cuddy. The regard the women were given by the ministers wife immediately counters the attitude shown by the one offered on the frontier. In the foyer he wants to tell of the hardship, but the cultured, caring woman asks him to please not speak of it. George Briggs is out of place here.

Bodies of water are often used to symbolize a rebirth or a purification. After all that they had been through, George Briggs was a new person. He began to care, and he wanted good things for people. In civilized Iowa he attempted to participate; it didn’t go well. The parsons wife was very polite, but once business was conducted she tells Briggs he can go now. After five grueling weeks it was all over, just like that. He went and got nicely dressed and attempted to sit in on a game of poker but was told his money was no good. Symbolically speaking, the vouchers of value that he earned on the frontier were told to be of no value. Then in clear language, he was told he was not welcome to sit in at the game. Western men are known for coming into town and sitting in at a game of cards. But in this civilization across the river, there wasn’t a seat for him, and his frontier money was literally no good. He had no value to them.

George Briggs learned to care about the women he was transporting, he had even tried once to cross a river, but he was followed by the women and had to turn back to help them. In short, he had left them behind, and couldn’t cross that river yet; the time for a crossing was still to come.

George Briggs learned to care about the women he was transporting, he had even tried once to cross a river, but he was followed by the women and had to turn back to help them. In short, he had left them behind, and couldn’t cross that river yet; the time for a crossing was still to come.

Once in the city he attempted to be respectable through dress and social engagement, and he even worked to bring dignity to the memory of Mary Cuddy by purchasing a tombstone, as well as buying shoes for a young lady and warning her of the frontier. But ultimately, having no luck, he gets drunk and boards a ferry back across the river. In keeping with the theme of water being the rebirth, he had been through it, and now returned to where he came from. The tombstone gets kicked off the ferry and floats down river, symbolizing all memory of Mary Bee Cuddy lost, and any attempt to record her struggle in life to be given up.

So as I said, the name George Briggs was not his real name. Like so many western characters that moved from one town to another they adopted a name to get by on. George Briggs wasn’t a real man, he was a symbol of all the men who came and went in the west, and could have never survived anywhere but the west. He gave a name that suited his situation, and then he encountered Indians, but survived, representing the trials of the earlier western men. Next he came upon a desperate character who would be ornery and fight for what he wanted with little regard for what anyone else wanted; this represented the proliferation of gun men on the range after the end of the civil war and the confinement of the Native Americans to reservations. He overcame that, too. Finally, he comes to a small hotel in the middle of nowhere. This represents the beginning of the end of the western character. Incredulously, these men of business have either no understanding of the code of the west, or they have no use for it, or probably even both. It was known on the frontier that when a stranger came to your door you gave them a meal, and if needed, a place to sleep. Here with this hotel were new ways of doing things, ways that were primarily concerned with a bottom-line benefit.

George Briggs couldn’t abide this; he represented a time and code that didn’t allow such un-neighborly behavior and so he cursed them (in period accurate swears) and then burned down their hotel. A purging fire to preserve his land.

Everything up to the initial ferry crossing at the river served to show who George Briggs was and what his world was about; fighting Indians, surviving desperate characters, not tolerating inhospitable eastern money-first ways; all these elements that prevailed against his life. He was able to overcome them all, but he could not overcome the one thing that lay just across the river, and that was civilization. It was only a matter of time before even that crossed into the west and George Briggs was no longer a welcome man anywhere. He left civilization, re-crossing the river, returning to what he knew, while firing shots at the city behind him, showing his contempt for their world. He would go out dancing and singing, embracing his time. And Mary Cuddy’s tombstone was let go of, drifting away. In the city he tried to be a different man, but returning to the frontier he would be what he really was, and it was the only time or place that he could have been who he was. George Briggs was the western character that disappeared towards the end of the 19th century.

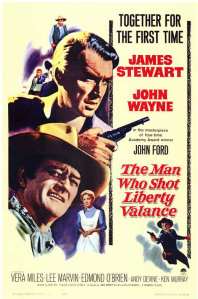

Starring Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne, this is one of John Ford’s later masterpieces. I love Ford because he brilliantly crafts stories, characters and cinematography in such a way that I come away not quite able to explain why I liked the movie so much. His craftsmanship is more subtle than Alfred Hitchcock’s and his movies not quite as epic as William Wyler’s. In an effort to understand why I like Ford movies so much I’ve actually started learning more about film. Not that I’m in danger of becoming a lofty film critic.

Starring Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne, this is one of John Ford’s later masterpieces. I love Ford because he brilliantly crafts stories, characters and cinematography in such a way that I come away not quite able to explain why I liked the movie so much. His craftsmanship is more subtle than Alfred Hitchcock’s and his movies not quite as epic as William Wyler’s. In an effort to understand why I like Ford movies so much I’ve actually started learning more about film. Not that I’m in danger of becoming a lofty film critic.

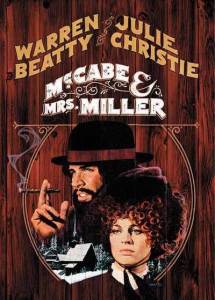

McCabe & Mrs. Miller is high on most lists of the greatest westerns of all time, especially as a prime example of the so-called revisionist western. As a fan of western movies, I would be remiss if I didn’t experience it. In honesty I didn’t expect to enjoy it as much as the sprawling, adventurous westerns that tend to be my favorites, but I had an open mind. My resulting experience was actually much more disappointing than expected. In its favor it is well-made and well-acted. On the other hand, there’s nothing at all to actually like about the film, at least for me.

McCabe & Mrs. Miller is high on most lists of the greatest westerns of all time, especially as a prime example of the so-called revisionist western. As a fan of western movies, I would be remiss if I didn’t experience it. In honesty I didn’t expect to enjoy it as much as the sprawling, adventurous westerns that tend to be my favorites, but I had an open mind. My resulting experience was actually much more disappointing than expected. In its favor it is well-made and well-acted. On the other hand, there’s nothing at all to actually like about the film, at least for me.

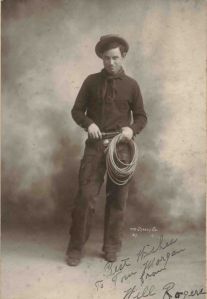

The Ropin’ Fool is a 20-minute silent comedy short starring American cultural icon Will Rogers. I had heard of the man because of his fame as a comedian and a political satirist, but was amazed to see – upon watching this short – that he was also a world-class roper. In fact, as I learned, his extraordinary lariat skills were what brought him to fame on vaudeville in the first place.

The Ropin’ Fool is a 20-minute silent comedy short starring American cultural icon Will Rogers. I had heard of the man because of his fame as a comedian and a political satirist, but was amazed to see – upon watching this short – that he was also a world-class roper. In fact, as I learned, his extraordinary lariat skills were what brought him to fame on vaudeville in the first place.

George Briggs learned to care about the women he was transporting, he had even tried once to cross a river, but he was followed by the women and had to turn back to help them. In short, he had left them behind, and couldn’t cross that river yet; the time for a crossing was still to come.

George Briggs learned to care about the women he was transporting, he had even tried once to cross a river, but he was followed by the women and had to turn back to help them. In short, he had left them behind, and couldn’t cross that river yet; the time for a crossing was still to come.