Which of the two is more accurate?

This is a question that I’ve seen asked over and over for many years on discussion boards and on Facebook. I used to see the question asked regularly on the IMDb message boards while they were still active. Unfortunately, the discussion never really involves any real logical debate but instead it’s usually just casting a vote for a person’s preference. And of course there is nothing wrong with whatever a person prefers, they’re both good movies with good qualities, but when we present the question and hinge it on the element of accuracy, are we really answering the question?

The first thing that should be understood is that you’re not comparing two movies of the same topic, though at first glance it’s understandable why the comparison is made. This is usually the first mistake when people want to debate this. Tombstone is a movie about the town of Tombstone and the troubles it had from its boom in 1879 to the relative end of the cowboy threat in 1882. Wyatt Earp, on the other hand, is a story about an individual who lived in the Old West and played a key role in several events of that time. So, right off the bat, we have to be clear in understanding that one movie is about a place, a town, a community, and a series of events; while the other is about a man and the study of his life and personal timeline.

Obviously, Wyatt Earp is central to the telling of his own story, so of course it makes sense that he is front and center. Wyatt arrived in Tombstone with his brother Virgil in 1879, and was key in many of the events that transpired there involving the Cowboys and general outlawry. He is a natural key element of that saga, as well, but we have to be discerning and recognize that while the Wyatt Earp movie is about Wyatt Earp, the Tombstone movie is about many people, Wyatt just being one of them. So with the Wyatt Earp movie we need elements pertinent to Wyatt Earp’s life, and in Tombstone the key is to have elements that are pertinent to the town…not necessarily to Wyatt Earp, the man.

One of the common complaints I hear about Tombstone from those who prefer Wyatt Earp is that Tombstone did not feature Warren and James, the other two Earp brothers. And one of the common complaints about the movie Wyatt Earp, from those who prefer Tombstone, is that the Tombstone outlaws, such as Curly Bill and especially Johnny Ringo, hardly get any consideration and are merely background characters. These are certainly legitimate and noticeable absences, but at the same time there is some valid reason for these varying approaches.

In the movie Tombstone, remembering that the movie is not about Wyatt but about the town and the cowboy troubles, Warren and James did not play significant roles. James was present tending bar at Vogan’s bowling alley, but he was not a combatant, and very rarely was ever involved in the heated troubles. Warren was involved a bit towards the latter part of the Earps time in town, and was a part of the vendetta ride, but he wasn’t present for a lot of the troubles, and most significantly he was not in town when the street fight happened.

Then when we look at the movie Wyatt Earp we see that we get healthy doses of both Warren and James, but we don’t get much understanding of Curly Bill and Johnny Ringo and the rest of the Arizona outlaws. We get the gunfight at the OK corral, as it’s called, but yet we don’t get the same background that we do from Tombstone, and to some this is a big disappointment.

When we keep in mind what each movie is trying to focus on, then we can better understand what is brought into focus on the screen, as well as why it’s really a fool’s errand to try to compare accuracy. Looking first at Tombstone, and the issue of being short a couple of brothers, we have to understand that the writer and director have a limited amount of time to present all the important elements that existed. If they were to tell the story of Tombstone and not give the audience a great understanding, and a well-rounded picture of characters like Curly Bill Brocious and Johnny Ringo, then we’d be shortchanged. These fellas were extremely key to everything that happened in Tombstone at that time. The Earp brothers Warren and James, while in town and close with Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan, were not key to the events as they transpired. Essentially, one has to act ask, does the absence of James and Warren compromise the understanding of the Tombstone troubles? Clearly the answer is: it does not. The story can still be told, and understood, without getting into Warren and James’ presence in town.

With Wyatt Earp we have the scope of 80 years centralized on one man’s life. The gunfight at the OK corral is very important in understanding Wyatt Earp, but the involvements of Curly Bill and Johnny Ringo, and their thieving activities, is not as crucial to understanding Wyatt Earp as it is to understanding the town of Tombstone in the early 1880s. I think it would be great if we could have more fleshing out of the Arizona outlaws, but I understand them not being a central focus in a story about Wyatt Earp when family was so important to him. We needed James and Warren in the movie Wyatt Earp more than we did in Tombstone, because in this study of the man we get a better picture of his relationship with his brothers and family, in general.

I use the example of the brothers involvement in Wyatt Earp, and the outlaws involvement in Tombstone to underscore the fact that these movies can’t be compared one-to-one. Wyatt Earp contains so much more time that it will naturally involve many elements that don’t have any place in the movie Tombstone, and the movie Tombstone is such an acute focus on such a short period of time and such a relatively small location, that it naturally would not include elements that are not germane to the story. This principle applies to more than just this sample, but can be used when looking at many of the two movies differences.

Each movie has a lot of great qualities, and any fan of the Old West, and especially of Wyatt Earp and the Tombstone saga, has a lot to enjoy from both movies, but when comparing the two, the comparisons should be based around personal enjoyment and the elicited emotional response; not the accuracy of two things with an inconsistent tether.

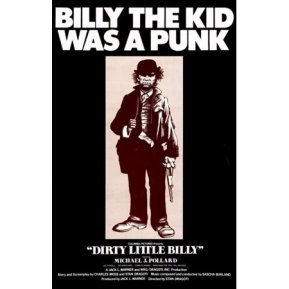

Out of this movement we got leads who were more and more jaded, who handled women however they wanted, and at it’s pinnacle we saw the most revered names of the gunfighter era dragged through the mud in attempt to “take the shine off”, as so many like to brag about when approaching the old west. Examples are “Doc” and “Dirty Little Billy”; each a blatant rewrite of history, intentionally skewed in order to serve a purpose of this “new vision” that satisfied the mood of the time. Which, of course, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the political overtones of the films that tied to the political activities of the country at that point in the countries history. I have no interest in getting into the politics of these movies, but it is an unavoidable part of this revisionist era of westerns. Another major aspect of the revisionist time was the Spaghetti Western. These films perfected the grizzled, S.O.B as lead character.

Out of this movement we got leads who were more and more jaded, who handled women however they wanted, and at it’s pinnacle we saw the most revered names of the gunfighter era dragged through the mud in attempt to “take the shine off”, as so many like to brag about when approaching the old west. Examples are “Doc” and “Dirty Little Billy”; each a blatant rewrite of history, intentionally skewed in order to serve a purpose of this “new vision” that satisfied the mood of the time. Which, of course, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the political overtones of the films that tied to the political activities of the country at that point in the countries history. I have no interest in getting into the politics of these movies, but it is an unavoidable part of this revisionist era of westerns. Another major aspect of the revisionist time was the Spaghetti Western. These films perfected the grizzled, S.O.B as lead character.

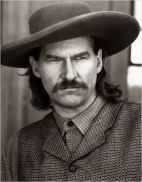

westerns, but after making a tremendous stamp on western movies as Wyatt Earp in 1993’s Tombstone, he returned to the genre in recent years, starring in Bone Tomahawk and the Hateful Eight. Couple that with a couple movies he did as a young man called the Longest Drive 1 and 2, and he’s certainly done enough to be considered a western movie favorite for today.

westerns, but after making a tremendous stamp on western movies as Wyatt Earp in 1993’s Tombstone, he returned to the genre in recent years, starring in Bone Tomahawk and the Hateful Eight. Couple that with a couple movies he did as a young man called the Longest Drive 1 and 2, and he’s certainly done enough to be considered a western movie favorite for today. KEVIN COSTNER

KEVIN COSTNER True Grit of 2010. This movie really puts Jeff Bridges into the category of a modern western leading man. He did a great job as Rooster Cogburn, and did an equally wonderful job as Wild Bill Hickok in 1995. Those two roles put him on the frontier map, but they’re anchored by the movies Bad Company (1972) and Hearts of the West (1975) when he was still a new actor on the scene, as well as with the modern-setting western Hell or High Water. Five movies with two very significant roles (Rooster & Wild Bill) definitely earn him recognition, but in a fun turn, we can cap him off with his portrayal in R.I.P.D., where he plays an old west marshal six-gunning against some unruly dead folks.

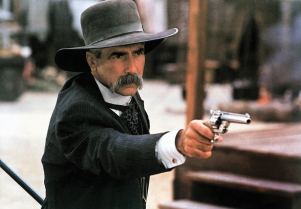

True Grit of 2010. This movie really puts Jeff Bridges into the category of a modern western leading man. He did a great job as Rooster Cogburn, and did an equally wonderful job as Wild Bill Hickok in 1995. Those two roles put him on the frontier map, but they’re anchored by the movies Bad Company (1972) and Hearts of the West (1975) when he was still a new actor on the scene, as well as with the modern-setting western Hell or High Water. Five movies with two very significant roles (Rooster & Wild Bill) definitely earn him recognition, but in a fun turn, we can cap him off with his portrayal in R.I.P.D., where he plays an old west marshal six-gunning against some unruly dead folks. Legend of Texas (1986), Quick and the Dead (1987), Conagher (1991), Gettysburg (1993), Tombstone (1993), The Desperate Trail (1994), Buffalo Girls (1995), The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky (1995), Rough Riders (1997), Big Lebowski (1998), Hi-Lo Country (Modern, 1998), You Know My Name (1999), The Ranch (TV Show, 2016). Yes, that’s right, I included the Big Lebowski. No, it’s not a western, but it’s significant that in that movie Elliott plays the conscious of the western pioneering spirit, juxtaposed against the lazy, jaded attitudes of today’s Los Angeles.

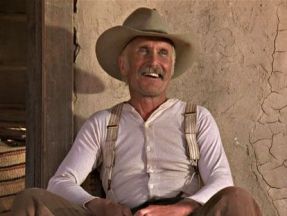

Legend of Texas (1986), Quick and the Dead (1987), Conagher (1991), Gettysburg (1993), Tombstone (1993), The Desperate Trail (1994), Buffalo Girls (1995), The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky (1995), Rough Riders (1997), Big Lebowski (1998), Hi-Lo Country (Modern, 1998), You Know My Name (1999), The Ranch (TV Show, 2016). Yes, that’s right, I included the Big Lebowski. No, it’s not a western, but it’s significant that in that movie Elliott plays the conscious of the western pioneering spirit, juxtaposed against the lazy, jaded attitudes of today’s Los Angeles. and likewise, Tom Selleck has peppered his whole career with the genre, consistently showing up on film in boots and cowboy hat, from the Sacketts in 1979, to Monte Walsh in 2003. My only complaint being that he needs to take a break from Jesse Stone to do another western or two; it’s about time! And, as with Sam Elliott, I’ll just post the list for the reader: Sacketts (1979), Concrete Cowboys (1981, TV Show), Shadow Riders (1982), Quigley Down Under (1990), Ruby Jean & Joe (Modern 1996), Last Stand at Saber River (1997), Crossfire Trail (2001) Monte Walsh (2003), Twelve Mile Road (Modern, 2003).

and likewise, Tom Selleck has peppered his whole career with the genre, consistently showing up on film in boots and cowboy hat, from the Sacketts in 1979, to Monte Walsh in 2003. My only complaint being that he needs to take a break from Jesse Stone to do another western or two; it’s about time! And, as with Sam Elliott, I’ll just post the list for the reader: Sacketts (1979), Concrete Cowboys (1981, TV Show), Shadow Riders (1982), Quigley Down Under (1990), Ruby Jean & Joe (Modern 1996), Last Stand at Saber River (1997), Crossfire Trail (2001) Monte Walsh (2003), Twelve Mile Road (Modern, 2003). JONES

JONES

GENE HACKMAN

GENE HACKMAN ED HARRIS

ED HARRIS Kiefer Sutherland

Kiefer Sutherland Val Kilmer

Val Kilmer Perhaps the most under-the-radar young-ish western actor of today is

Perhaps the most under-the-radar young-ish western actor of today is  Finally,

Finally,  done two westerns to date, but they’re good ones to be in. First playing Billy Clanton in Tombstone, and then starring with Robert Duvall in Broken Trail. Some have criticized his stiffness in the latter of the two movies, but considering that most cowboys were hard working roughnecks, and not camp cut-ups, his performance comes off appropriately stoic. The final entry is perhaps the last name one might expect, but given his new avenue towards westerns, including three western movies in two years, it’s nice to see this turn in direction. Ethan Hawke first starred in A Valley of Violence in 2016, a spaghetti-western styled film, then co-featured in the recent remake of The Magnificent 7, and is slated to star in a movie about a kid who witnesses the encounter between Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, conveniently titled The Kid.

done two westerns to date, but they’re good ones to be in. First playing Billy Clanton in Tombstone, and then starring with Robert Duvall in Broken Trail. Some have criticized his stiffness in the latter of the two movies, but considering that most cowboys were hard working roughnecks, and not camp cut-ups, his performance comes off appropriately stoic. The final entry is perhaps the last name one might expect, but given his new avenue towards westerns, including three western movies in two years, it’s nice to see this turn in direction. Ethan Hawke first starred in A Valley of Violence in 2016, a spaghetti-western styled film, then co-featured in the recent remake of The Magnificent 7, and is slated to star in a movie about a kid who witnesses the encounter between Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, conveniently titled The Kid.

Lake’s book is certainly due its fact-checking, and there are some things he got wrong, but keep in mind that his primary source died early on in the development of the project. On top of that he was working in a time without internet, or easy phone calling and records like we have today. The very fact of how much the Lake Notes at the Huntington Library are referenced by today’s researchers shows how much value his work holds. The main fault against Lake is that he invented dialogue attributed to Wyatt, who was known widely for his laconic nature.

Lake’s book is certainly due its fact-checking, and there are some things he got wrong, but keep in mind that his primary source died early on in the development of the project. On top of that he was working in a time without internet, or easy phone calling and records like we have today. The very fact of how much the Lake Notes at the Huntington Library are referenced by today’s researchers shows how much value his work holds. The main fault against Lake is that he invented dialogue attributed to Wyatt, who was known widely for his laconic nature.

This knowledge of Stuart Lake is helpful in the study of Wyatt Earp, but what of the lawman himself? Well, Lee Silva does an amazing job here, too. He deftly shows, time after time, that the claims Wyatt made, often interpreted as bluster by the detractors, were true if just researched deeply enough. Take for example Wyatt’s claim about being one of the men who answered the call to a Camp Cadiz when he was a late teen in Southern California. The anti-earpers have used this as an example of Wyatt making stuff up to inflate his importance, but Silva, through his mastery in research, points out that there was a Camp Cady, often referred to as Cady’s. Then with additional details, shows that Wyatt was much more likely than not telling the truth.

This knowledge of Stuart Lake is helpful in the study of Wyatt Earp, but what of the lawman himself? Well, Lee Silva does an amazing job here, too. He deftly shows, time after time, that the claims Wyatt made, often interpreted as bluster by the detractors, were true if just researched deeply enough. Take for example Wyatt’s claim about being one of the men who answered the call to a Camp Cadiz when he was a late teen in Southern California. The anti-earpers have used this as an example of Wyatt making stuff up to inflate his importance, but Silva, through his mastery in research, points out that there was a Camp Cady, often referred to as Cady’s. Then with additional details, shows that Wyatt was much more likely than not telling the truth. On this alone the book could probably be considered a must for Earp research, but what Hornung does by extension that is so important is that he doesn’t just lay out some interesting facts. Rather, that the culmination of these facts show Wyatt Earp to have been a lawman working in the scope of the law and working for the benefit of law and order. Some have considered him a lawless assassin seeking revenge. The facts show that he was a strongly supported agent of the law, and this is very crucial to the legacy of Wyatt Earp, and should definitely be read when forming an idea of who Wyatt Earp was and what his life was about.

On this alone the book could probably be considered a must for Earp research, but what Hornung does by extension that is so important is that he doesn’t just lay out some interesting facts. Rather, that the culmination of these facts show Wyatt Earp to have been a lawman working in the scope of the law and working for the benefit of law and order. Some have considered him a lawless assassin seeking revenge. The facts show that he was a strongly supported agent of the law, and this is very crucial to the legacy of Wyatt Earp, and should definitely be read when forming an idea of who Wyatt Earp was and what his life was about.